Throughout the 19th century, New York’s Morgan Iron Works was a leading manufacturer of marine steam engines. Founded in 1838 as T. F. Secor & Co., it was later acquired and expanded by investor Charles Morgan. In its first three decades, the company produced over 140 engines. While not environmentally friendly, it played a crucial role during the U.S. Civil War. Learn more on new-york.name.

Founding and Early Days of T. F. Secor & Co.

The T. F. Secor and Co. marine engine plant began operations on 9th Street in New York City in 1838. It was founded by T. F. Secor, William K. Colkin, and Charles Morgan, who were equal partners in the enterprise.

Morgan also held shares in sailing vessels but sold them in 1845 when the U.S. Congress established subsidies for American shipping-related businesses. Seizing the opportunity, Morgan decided to invest heavily in T. F. Secor & Co. and proposed an expansion to his partners. They agreed, and the plant’s facilities grew to occupy another block and a half between 8th and 10th Streets.

The factory employed around 700 people, producing engines for both coastal and ocean-going steamships. Manufacturing processes were far from modern environmental standards, which were not a concern at the time. However, this industry was vital to New York City’s economy, and its growth was supported by the city government.

The Era of Morgan Iron Works

In 1847, Charles Morgan’s son-in-law, George W. Quintard, took charge of the company’s financial department. Three years later, Morgan bought out his partners’ shares, and the plant was renamed Morgan Iron Works. Quintard became its manager, while Morgan served as its financier.

A major upgrade program for the plant followed. This included the installation of steam hammers, a floating steam derrick, and other heavy machinery. A new shipyard was also built on the East River, significantly reducing public access to the waterfront. Quintard suggested diversifying the company’s output to include equipment for sugar mills and pumps for water supply companies.

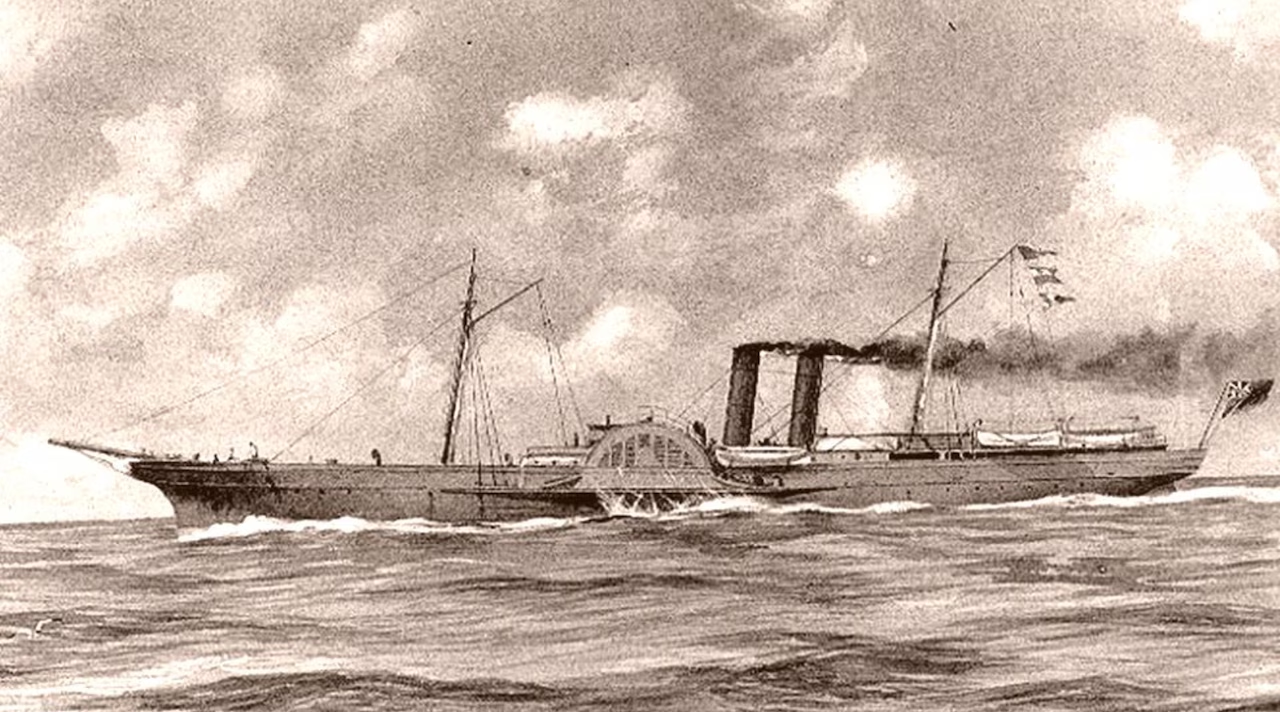

Interestingly, the plant’s primary customer was Charles Morgan himself. He owned a shipping business and commissioned the steamships *San Francisco* and *Brother Jonathan* from the company. In 1852, he decided to replace five of his older ships and ordered new engines from Morgan Iron Works. From then on, he sourced all his engines exclusively from the plant, ensuring a steady stream of work.

By the start of the Civil War, the company had become one of the leading steam engine manufacturers in the United States. It specialized in engines for coastal and river service, and its products were used by numerous steamship lines.

The Role of Morgan Iron Works in the U.S. Civil War

In 1858, the plant secured its first naval contract for the steam-powered warship USS Seminole. Despite facing accusations of government favoritism, the owners managed to dismiss the charges. They began to pursue more military work, anticipating that demand would continue to grow.

However, the start of the Civil War was a disaster for Charles Morgan. The Confederacy immediately captured his entire fleet, which was stationed in the Gulf of Mexico. The entrepreneur recovered quickly from this blow and focused his efforts on the operations of Morgan Iron Works.

The war caused a surge in demand for ships, engines, and shipyards. Like its competitors, Morgan Iron Works capitalized on this opportunity, producing 38 engines for U.S. ships and even collaborating with the Italian Navy. In the U.S., ships equipped with the company’s engines included:

- USS Ticonderoga,

- USS Wachusett,

- USS Ascutney,

- USS Ammonoosuc.

By the end of the war, the company had grossed over two million dollars from naval contracts. Unfortunately, the owners had no intention of reinvesting any of these profits into improving production, working conditions, or community development.

The Company’s Later Years

After the war, the U.S. government began selling off hundreds of now-unnecessary ships, leaving marine engine builders and shipyards with virtually no work. Most companies in the industry quickly went bankrupt, with the notable exceptions of Morgan Iron Works and Etna Iron Works, which was run by John Roach. Roach managed to stay afloat by diversifying his production to include machine tools.

As for Morgan Iron Works, the company struggled and had almost no orders for engines. Over several years, it produced only two. The business survived thanks to Charles Morgan’s personal wealth, but in 1866, he suffered additional financial losses that put the company in jeopardy.

At this time, John Roach decided to venture into shipbuilding and repair and began looking for a suitable shipyard. In 1867, he offered to buy Morgan’s company for $450,000. To finance the purchase, he took out two mortgages and paid a quarter of the sum in cash. Roach soon defaulted on the payments, but Morgan did not foreclose, and the debt was eventually paid off.

John Roach thus became the new owner of the plant and shipyard, effectively creating a monopoly in shipbuilding and engine manufacturing. He closed his own Etna Iron Works and transferred its best personnel and equipment to the East River location. Under his leadership, Morgan Iron Works was reborn as a leading U.S. manufacturer of steam engines. The shipyard continued to pollute the river and the surrounding area, but it was profitable and formed the cornerstone of Roach’s business empire.

Roach also acquired a shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. After modernization, the Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works also became a well-known and productive facility. It operated until the 1880s and had its own engine manufacturing plant. Morgan Iron Works continued to operate in parallel. Its production line was expanded to include ship furniture and plumbing. The name “Morgan Iron Works” was retained, even after the company became part of the new “John Roach & Son” corporation.

When workers began to fight for their rights, better conditions, and higher pay, John Roach would shift work from one shipyard to another during strikes. Fortunately for him, the strikes never occurred at both locations simultaneously, but he was still forced to partially concede to the workers’ demands. As for environmental standards, they were never implemented at the facilities.

In 1885, John Roach retired. He initially placed his business into receivership, and it was later taken over by his sons. They kept both shipyards and continued to manage them in their father’s style. After John Roach passed away in 1908, his descendants decided to exit the shipbuilding industry. Shortly thereafter, the shipyards and Morgan Iron Works were closed for good.

Over time, the buildings of the former Charles Morgan plant were converted into apartment houses. In 1949, the site of the once-mighty enterprise was redeveloped into a housing complex that still stands in the 21st century. Today, no trace remains of the massive and polluting factory, and residents of this New York neighborhood now enjoy views of the river.