He dedicated his life to finding, studying, and preserving the last wild places on the planet. Alan Rabinowitzwas a scientist who transformed the jaguar legend into scientific reality and a symbol of wild forest conservation. His life is the story of a man who didn’t just observe nature but built bridges between the human world and the world of big cats. Read on new-york.name to learn how Alan Rabinowitz traveled the path from a boy who couldn’t utter his own name to a man who spoke on behalf of entire species.

The Boy Who Found His Voice Among Jaguars

Alan Robert Rabinowitz was born on December 31, 1953, in Brooklyn, to Shirley and Frank Rabinowitz, Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. When the boy was only five years old, he developed a severe stutter. His body would spasm every time he tried to utter a word. At school, despite having excellent grades, Alan was considered a troubled child and sent to classes for students with developmental disabilities. Peers teased him, and teachers often didn’t know how to react.

The boy was most afraid of speaking aloud and sometimes even injured himself to avoid speaking in front of the class. It was then that Alan began to retreat into his own world—a dark closet where he kept turtles and hamsters. Only there could he speak freely to the animals, who seemed to understand him.

One day, his father, a gym teacher, took him to the Bronx Zoo. The boy froze in front of the cage of a solitary jaguar. He confessed his fears to the animal—the shame and pain he couldn’t express to people. The animals became his language and his meaning in life. Rabinowitz often said:

“Even the most powerful among them have no voice, they are not understood—and all they want is just to live.”

This very thought later defined his calling. His teenage years were difficult. The young man was teased and responded with punches; the boxing skills his father taught him came in handy. At 18, Alan learned about Hal Starback’s clinic in Geneseo, where they taught stutter control. It was there that he spoke a full sentence without fear for the first time.

“I was no longer helpless,” he recalled. “I learned to speak, but the real healing came later.”

After high school, Rabinowitz enrolled at Western Maryland College (now McDaniel College), where he earned a bachelor’s degree in biology and chemistry. His love for animals blossomed into science. He continued his education at the University of Tennessee, where he earned master’s and doctoral degrees in ecology. His first scientific paper on black bears and raccoons caught the attention of legendary biologist George Schaller, who invited the young researcher to join an expedition to Belize. This marked the beginning of a great journey.

“I lived in two worlds,” he said. “In the world of people, I was an eccentric, but among animals, I was myself.”

The stutter that was once his prison, he called a gift—something that taught him compassion, resilience, and the ability to hear those whom others overlook.

His childhood whisper to the jaguar in the cage transformed into a powerful voice for science and nature conservation—a voice that continues to resonate even after his death.

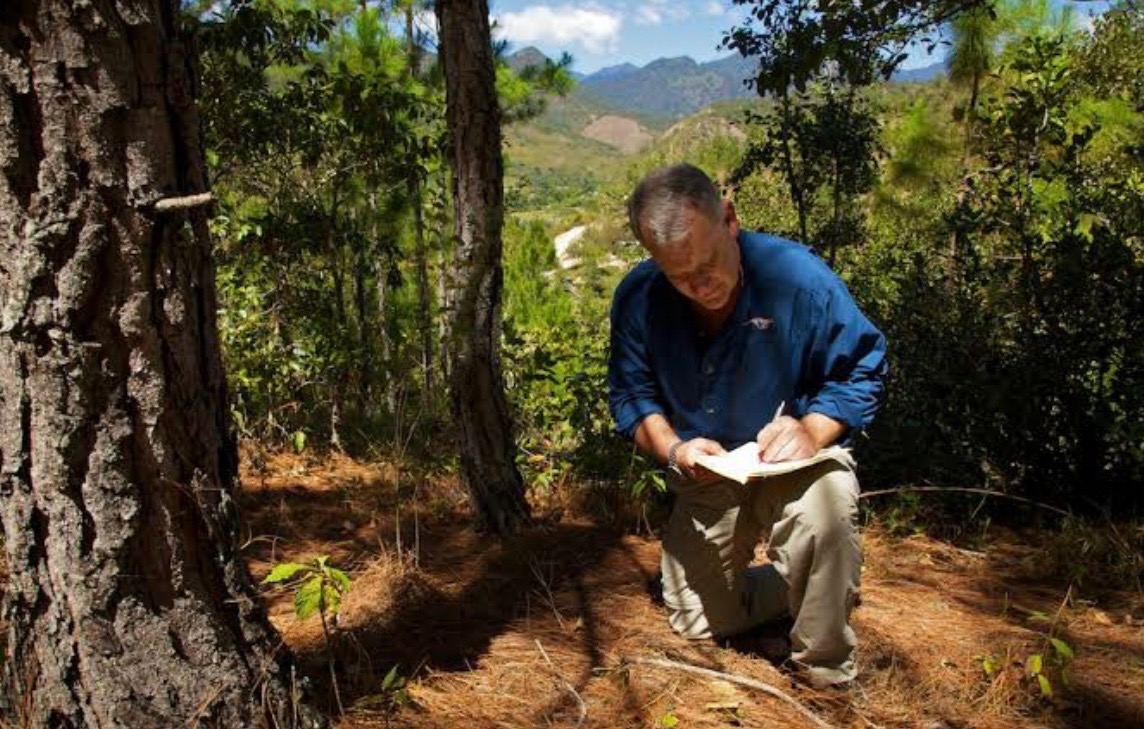

The Traveler Across the World’s Wild Frontiers

After graduating from the University of Tennessee, Rabinowitz joined the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). He worked there for nearly three decades, eventually heading the Science and Exploration Division. At the WCS, he became a scientist capable of combining field research, strategic thinking, and conservation policy.

His early projects focused on raccoons and black bears, but his scientific horizon quickly expanded—to the big cats of Asia and Latin America, to rhinos, bears, and rare small predators.

In the 1990s and 2000s, Myanmar became Rabinowitz’s second scientific homeland. It was there that he conducted some of his most important research. Rabinowitz discovered four new mammal species, including the most primitive deer species known to science (Muntiacus putaoensis), and initiated the creation of five new protected areas. These include the country’s first marine national park (Lampi), Hkakaborazi National Park (Myanmar’s largest mountainous protected area), the Hukawng Valley Wildlife Sanctuary, and the formation of the huge Northern Forest Complex, spanning over 5,000 square miles. Thus, Rabinowitz effectively helped Myanmar establish a modern conservation system.

Despite his love for animals, Rabinowitz stressed that there must always be a boundary between humans and wild nature. In his field observations, he often encountered dangerous situations—as in Belize, when tracking large predators while working on the Cockscomb sanctuary. For him, such moments were not romantic stories but reminders that humans are guests in the wild world.

Over the years, Rabinowitz moved away from the traditional model of a “people-free reserve.” He realized that animals need large territories and natural corridors, meaning people cannot simply be excluded. Local communities are the key to conservation, and nature protection works when it benefits people.

He often cited the example of Belize. Local residents once killed large predators, but over time, they became their protectors because tourism brought in more money than logging.

Alan Rabinowitz was a scientist who combined deep field expertise, diplomacy, conservation strategy, and the ability to see the world systemically. He researched and protected the world’s most vulnerable ecosystems—from Central America to the Himalayas and Southeast Asia. His work showed that nature conservation is not about “walling off the world,” but about creating a harmonious interaction between people, animals, and landscapes.

The Fight for the Future of Jaguars

When Rabinowitz first entered the tropical jungles of Belize, he saw how quickly the places where jaguars could roam freely were disappearing. In 1986, he created the world’s first jaguar sanctuary—the Cockscomb Basin Wildlife Sanctuary. This was a breakthrough in conservation history. The area, spanning over 200 square miles, became a haven for about 200 jaguars, who had been on the verge of extinction until then.

His idea later grew into something much larger—the “Jaguar Corridor,” stretching from Mexico to Argentina. He saw this animal not just as a predator but as the guardian of the balance of entire ecosystems.

“By saving the big cats, we save the landscapes,” Rabinowitz said. “And with them—all living things, including ourselves.”

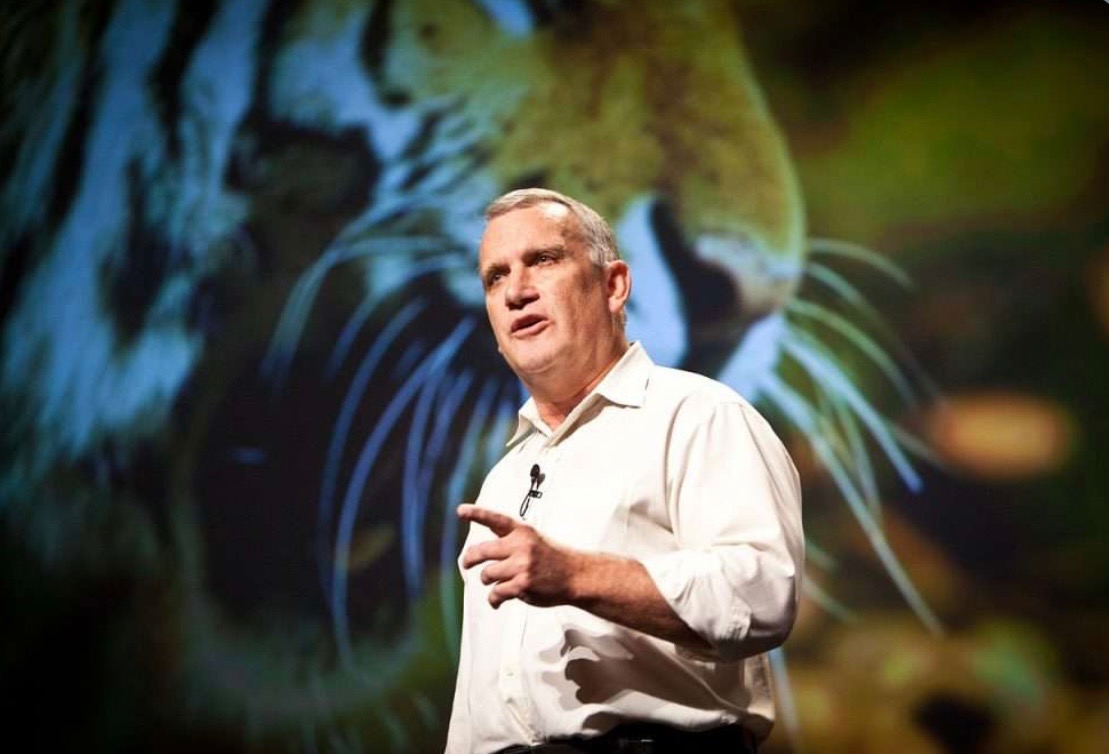

Under his leadership, Panthera, the organization he co-founded in 2006, launched conservation programs for not only jaguars but also tigers, lions, pumas, cheetahs, and snow leopards. However, the jaguar remained for the scientist a sacred symbol of nature that connects cultures and continents.

In 2018, the Alan Rabinowitz Research Center was opened in Belize. It continues the world’s longest-running jaguar observation: over 30 scientific papers and decades of collaboration with local communities have transformed the area into a living laboratory of coexistence.

His colleagues at Panthera continue the scientist’s work, protecting the Maya Forest Corridor—a narrow strip of jungle that connects the jaguar habitats of Belize, Mexico, and Guatemala. This territory is the last link maintaining the species’ single genetic flow.

Alan Rabinowitz believed that the jaguar is not just an animal but an ancient spirit that unites the forest, the land, and humans. His “corridor” is humanity’s path toward harmony with the wild.

The Legacy of a Great Scientist

In 2001, Alan Rabinowitz was diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Despite the illness, he did not cease his expeditions, lectures, and fight for the wild cats. And even as his body weakened, his will only grew stronger.

On August 5, 2018, Alan Rabinowitz died of cancer, leaving behind not just dozens of conservation projects but an entire philosophy of human-wildlife coexistence. Conjour magazine called his legacy “an inspiration to all who fight for the big cats.”

Rabinowitz left behind over a hundred scientific and popular articles, as well as eight books that chronicled his life between civilization and the wild. Among them:

- Jaguar: One Man’s Struggle to Establish the World’s First Jaguar Preserve (1986).

- Chasing the Dragon’s Tail: The Struggle to Save Thailand’s Wild Cats (1991).

- Beyond the Last Village: A Journey of Discovery in Asia’s Forbidden Wilderness (2001).

- Life in the Valley of Death: The Fight to Save Tibet’s Last Great Cats (2008).

- An Unspoken Contract: My Life with the Jaguar (2014).

- A Boy and a Jaguar (2014)—a moving children’s book about a boy who stuttered but learned to speak to animals with his heart.

Alan Rabinowitz was the subject of the PBS/National Geographic film In Search of the Jaguar and the BBCdocumentary Lost Land of the Tiger, filmed in Bhutan.

In his autobiography, the scientist wrote:

“I lived in caves, trapped and tracked bears, jaguars, tigers, and rhinos. I discovered new species of animals, documented lost cultures. But inside me, the same little boy who was once afraid to speak always lived. And it was he who gave me the strength to speak for those who cannot.”

His story became a source of inspiration for thousands of people with speech disorders—proof that a weakness can turn into a calling.

Alan Rabinowitz’s name stands alongside the greatest wildlife defenders of the 20th and 21st centuries. He left behind reserves, scientific discoveries, and an entire army of followers who continue his work. His jaguar continues its journey through the forests of the Americas—a living symbol that the true voice of nature never disappears.